Predicting the Future of Oil Prices - Lessons from History's Biggest Oil Shocks

Prepared by:

Black Gold

The Oil Shock of 1973–1974

The price of oil nearly quadrupled to $11.65 per barrel

The Oil Shock of 1978–1979

The second oil shock of the 1970s was fuelled by strong global oil demand and Middle East events, much like its 1973–74 predecessor. The Iranian Revolution began in early 1978 and ended a year later with Sheikh Khomeini taking control of the Islamic Republic as the ultimate religious leader. The Iranian oil output declined by 4.8 million barrels per day (7% of world production at the time). Fear of more disruptions following the reduction in Iranian oil output led to widespread speculative hoarding. A booming global economy and a sharp increase in precautionary demand were responsible for much of the increase in the cost of oil during the crisis. Fearful of undermining fragile economic growth, the FOMC refrained from raising interest rates too sharply, even as public and FOMC members expressed growing concerns about the weakening dollar and accelerating inflation. Paul Volcker, the newly appointed Fed chairman, had been a fervent supporter of using monetary policy to combat rising inflation. In addition to successfully guiding the Fed to raise the federal funds rate from 11 percent when he took office to a peak of 19 percent in 1981, Volcker oversaw the adoption of policy measures that reduced the rate of twelve-month inflation from a peak of nearly 15 percent to 4 percent by the end of 1982. Even though the Fed’s determination under Volcker was successful in bringing down inflation, the monetary contraction and the effects of the oil price shock caused the economy to enter the worst recession since the Great Depression. The oil crisis eventually came to an end because of investments made in energy-saving technologies and additional energy production, as well as a slowdown in economic activity in industrialized nations, a decline that would last for much of the next twenty years.

Iranian oil output declined by 4.8 million barrels per day.

Gulf Wars and Big Oil (1990-1991; 2003-2011)

Iraq ranks 5th in the world for oil production. When Iraq attacked Kuwait in 1990, the official reason was that Kuwait was overproducing oil intentionally so that Iraq would be incapable of holding its ground economically. The attack of Iraq on Kuwait raised the oil price from $34 to about $77 per barrel. In the second Gulf War from 2003 to 2010, one day after the United States and its allies launched a massive attack on Iraq, oil prices in New York plunged an unprecedented $10.56 a barrel to $21.44. War doubled the price of oil in both Gulf wars. Oil is nevertheless critical to understanding the decision to invade Iraq and remove Saddam Hussein from power. Oil did not make a U.S. war against Iraq inevitable. But it did much to set the stage for war, greatly increasing the incentives to topple Saddam by any means possible. Before the 2003 invasion, Iraq’s domestic oil industry was fully nationalized and closed to Western oil companies. Nowadays, it is largely privatized and utterly dominated by foreign firms. From ExxonMobil and Chevron to BP and Shell, the West’s largest oil companies have set up shop in Iraq. Fed up with foreign firms, a leading coalition of Iraqi civil society groups and trade unions, including oil workers, declared on February 15 that international oil companies have “taken the place of foreign troops in compromising Iraqi sovereignty” and should “set a timetable for withdrawal.

Both Gulf Wars saw the price of oil nearly double.

9/11 Terrorists Attacks (2001)

Brent Crude rose and then quickly fell.

Israel and The Axis of Resistance War

Brent prices increased by about 4% after the terrorist attacks in Israel on October 7th, 2023 before subsequently stabilizing, 1% on April 13th after Iran attacked Israel with 200 missiles, and dropped 4% on October 15 after media reports Israel would not strike Iranian oil targets, easing fears of a supply disruption. Israel is not an oil producer itself but a key player in Middle Eastern politics. The latest US sanctions on Iran will impact China, a country that purchases over 95% of Iran’s exported oil. “With 23 vessels being sanctioned at one go, it is going to be challenging for dealers to find alternative carriers and redo administration works,” said Sijia Sun, associate director for downstream research and analysis at Commodity Insights. Iran has frequently threatened Western and regional nations to blockade the Strait of Hormuz in the Persian Gulf, where 20% of the world’s oil trade passes. However, this move will upset China, and it is highly unlikely. Most of the oil passing through the Strait is destined for Asia and does not directly impact the Western nations. Some fear oil prices could reach $200. “If Israel takes out oil Installations in Iran, easily oil prices could go to $200 plus,” Bjarne Schieldrop, chief commodities analyst at Swedish bank SEB, told US broadcaster CNBC last week. Excess capacity keeps oil prices in check for now (the US and Saudi Frenemy relationship- the Saudis can always pump more). However, prices could go up quickly in the event of a wider regional war. That would put the U.S. and Western Europe in a recession worse than 2008 and the earlier oil shock of 1974. Iran’s air defences are substantial. However, the major destruction of key pipelines could disrupt Iranian oil flows for weeks or even months. Cyberattacks could also disrupt the control systems of refineries, pipelines, and export terminals, leading to shutdowns or damage that require extensive repairs. Theoretically, if Israel attacked Iran’s infrastructure, Saudi Arabia could compensate for any shortage in the world’s oil supply. However, the kingdom’s main oil fields could become vulnerable to Iran’s proxies’ attacks.

“Oil is not as important in energy consumption as it was in the ’70s. Back then, it used to meet 50% of our energy needs worldwide,” said Nakhle. “The Middle East is no longer the only producer,” she added, noting how increased production by the United States, Brazil, Canada and Guyana has helped diversify supplies.

Because of the potential damage to the global economy, Israel will likely hit military installations. At the same time, there is no communication between the two sides, so the margin of error is very high. For Middle Eastern countries, the risk channel clearly dominates oil prices increase because traders expect disruptions to future oil supplies, therefore increasing volatility.

Some fear oil prices could reach $200.

Does History Predict the Future?

According to the paper “The Effects of Terrorism and War on Oil Prices -Stock Indices Relationship” by Christos Kollias, prolonged wars have long-lasting effects on the stock markets, whereas markets are more efficient in absorbing the effects of terrorist attacks. The relationship between stock markets and oil prices can be positive or negative. Increases in oil prices invariably lead to higher transportation, production, and heating costs, which can drag corporate earnings. Higher oil prices affect inflation expectations and curtail consumers’ discretionary spending. Inflationary pressure may then lead to upward pressure on interest rates and, through this channel, affect economic activity and stock price valuations. On the other hand, investors may associate increasing oil prices with a booming economy. Increases in oil prices have a negative impact on stock returns in the US and twelve European countries. This, however, is not the case for the stock market in Norway, an oil-exporting country. As conflict and terrorist actions have become more regular, oil stock prices do not increase in response to conflict. During periods of supply constraints, however, oil prices may react more significantly.

Oil prices may be impacted by geopolitical shocks due to decreased economic activity or increased risks to the supply of commodities. Tensions increase uncertainty about the economic outlook, which negatively affects consumption and investment and potentially disrupts international trade. Furthermore, the risk channel refers to how financial markets account for heightened future risks to oil supply, extending beyond the immediate geopolitical shock and incorporating potential long-term disruptions into current pricing.

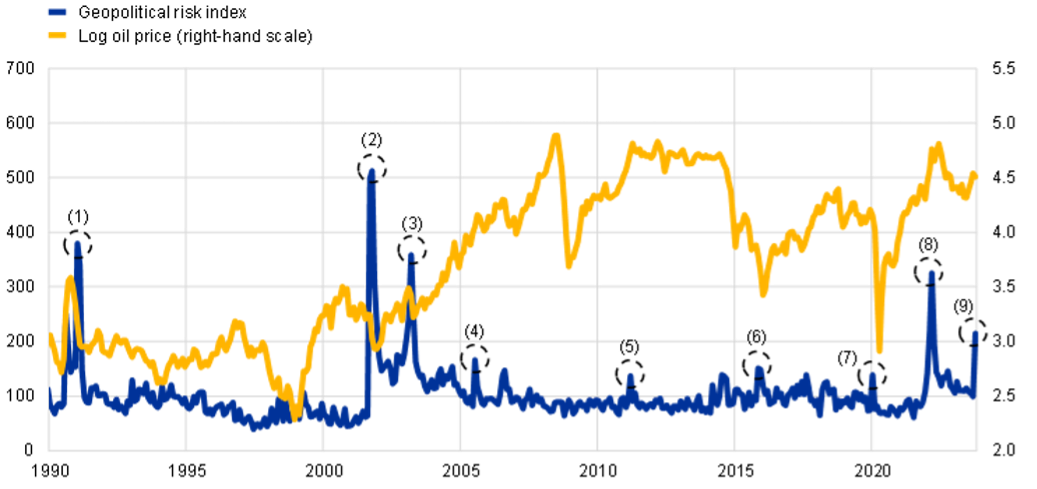

Oil Prices and Geopolitical Risk Since 1990

Disclaimer

About Confluence

We resolve complex data challenges

As the investment management industry deals with ever-present data challenges along with increasing demands from clients and regulators to provide more detailed data and granular analysis, we help our clients transform their raw data into meaningful insights, providing solutions to complex data challenges.