New in RegTech:

What investment firms can expect in the EU, in 2025 and beyond

After last month’s edition on what investment firms can expect in the US’s new regulatory climate, let’s now turn to Europe. At the leadership level, the timelines align: both Trump and the European Commission President have terms that extend until 2029. But the similarities end there, as regulatory fragmentation and change should continue to characterize the EU for the several years to come.

An active Commission with a renewed mandate

First, some context. The European Commission, essentially the EU’s executive branch, wields formidable power in the EU. It has the sole power to introduce legislation, rendering the European Parliament and Council mere “vetoing bodies”. (In fact, in certain circumstances, as seen during the COVID pandemic and energy crisis, the Commission can bypass Parliament altogether, passing legislation with only the Council’s approval.)

Within the Commission, power is largely centralized in its President, who, in agreement with the Council, appoints the 27 Commissioners (one from each EU Member State), delegates to each Commissioner a policy area portfolio, and essentially sets the agenda for the EU. Thus, Ursula von der Leyen, who in July won a second five-year term as Commission President, is in many ways the most powerful person in Europe.

On the day of her re-election, von der Leyen immediately released the Commission’s 2024-2029 agenda, which announced the development a new EU “Savings and Investments Union”. Conceived by former Italian Prime Minister Enrico Letta -- in a 146 page report published in April that calls the current Capital Markets Union “incomplete” and recommends a fuller integration of financial services -- the Savings and Investment Union aims to mobilize private capital into the EU. Many of Letta’s other recommendations, such as streamlining regulation, accelerating the digital and green transitions, and prioritizing research and innovation, are also echoed in von der Leyen’s agenda.

Last month, von der Leyen’s unexpected choice for “Commissioner for Financial Services and the Savings and Investment Union”, Maria Luís Albuquerque, was formally approved by Parliament. All the political parties, except those furthest left and right (The Left and The Europe of Sovereign Nations, respectively), supported her. More on Parliament’s political challenges further below.

A former Portuguese finance minister, Albuquerque had sacrificed political capital in Portugal by supporting EU austerity measures to position the country as a “good pupil”. Her investment management experience, her reputation as being knowledgeable and welcoming to financial services (unlike her portfolio predecessor Mairead McGuiness), and her center-right political ideology puts her squarely in-line with von der Leyen’s second-term plans for Europe.

Von der Leyen’s tasks for Albuquerque state, in part:

- “You will develop a Savings and Investment Union”

- “You should tackle the fragmentation of capital markets by helping design simple and low-cost saving and investment products at EU level”

- “I want you to review the regulatory framework to ensure that innovative, fast growing European companies and start-ups can finance their expansion here in Europe”

- “You must contribute to reducing reporting obligations by at least 25% - and for SMEs by at least 35%”

- “You should explore how to scale up sustainable finance”

- “You should further develop the Banking Union”

- “You should continue work on improving digital finance and payments to support new technologies in our financial system”

- “I want you to assess artificial intelligence deployment in the financial sector”

EU jargon: confusing “Councils”

Council of the European Union. Often referred to as “the Council of Ministers,” or the “Council of the EU”, or simply “the Council”. The Council of the European Union is one of two bodies of the EU’s legislative branch, the other being Parliament. Most EU legislation requires adoption both by the Council and the Parliament.

- Composition: Meets and votes in different configurations, based on policy area (such as foreign affairs, economy and finance, and environment). For each configuration (currently there are ten), there are 27 voting Council members: the policy-relevant government ministers from each EU country.

European Council. The European Council adopts “conclusions” that define the EU’s strategic direction and priorities. It also proposes the Commission President (who must be approved by Parliament). It has no legislative power.

- Composition: 27 voting members, being the heads of state of each EU country. A separate European Council President, as well as the Commission President, are non-voting members.

Council of Europe. An international human rights organization; not an EU institution.

Parliament’s center is weakened, but should hold for now

Notwithstanding the Commission’s power, Parliament retains important checks on it. As one of the two main EU legislative bodies (the other being the Council), Parliament must approve the Commission’s proposed laws, absent special circumstances as mentioned earlier. And every term, Parliament must approve the new slate of Commissioners as well as the President. Further, Parliament retains the right to dismiss the entire Commission with a vote of no confidence.

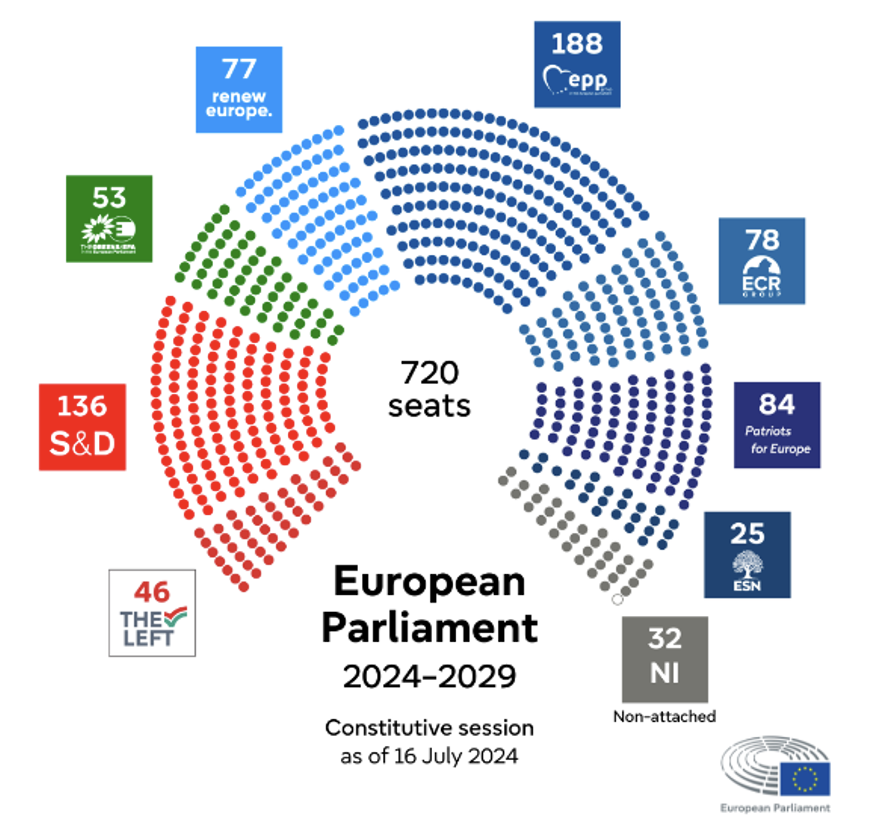

It follows that Parliament will be important to what von der Leyen – and the EU generally -- can achieve legislatively in the next 5 years. Her re-election as Commission President, in July, came on the heels of the European Parliamentary elections the month prior. Ideologically aligned with the center-right European Peoples’ Party (EPP), von der Leyen might have been pleased with EPP’s gain of 12 seats, keeping it as the largest bloc, while parties to her left Renew and the Greens suffered major losses of 25 and 19 seats respectively.

But those successes were tempered by an underlying populist discontent – that had already presented itself across the continent in domestic politics -- which inevitably bubbled to the surface at the EU level. Right-wing factions made strong Parliamentary gains, and some of them immediately merged to form Patriots for Europe (PfE), now suddenly the third-largest party in Parliament. Meanwhile the right-wing European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) gained 9 seats to become the fourth-largest party, and separately a contingent of extreme-right nationalist Members of Parliament joined up to form the 25-seat Europe of Sovereign Nations (ESN) party.

Instinctively euro-skeptic, the three parties PfE, ECR and ESN represent a growing threat from von der Leyen’s right. Combined with the heavy losses of the Greens and Renew, it means her EPP -- and possibly her EU agenda – would need to cater more to the traditional left Socialists and Democrats (S&D), which remains the second-largest party (having lost 3 seats), in order to build majority consensus without having to concede to the right flank.

So, while it appears that von der Leyen still has the numbers for productive coalition-building in Parliament – which would of course need to approve her Commission’s proposals -- her aims could be diluted somewhat during legislative negotiations.

The Draghi report

It was at the official request of von der Leyen that Mario Draghi -- the former ECB head once lauded as “Super Mario” for helping save the eurozone during the sovereign debt crisis -- produced a detailed report on European competitiveness. Released in September, and close to 400 pages, it suggests a new crisis. Building on the Letta report, Draghi paints a sobering picture of the EU’s weakening global standing.

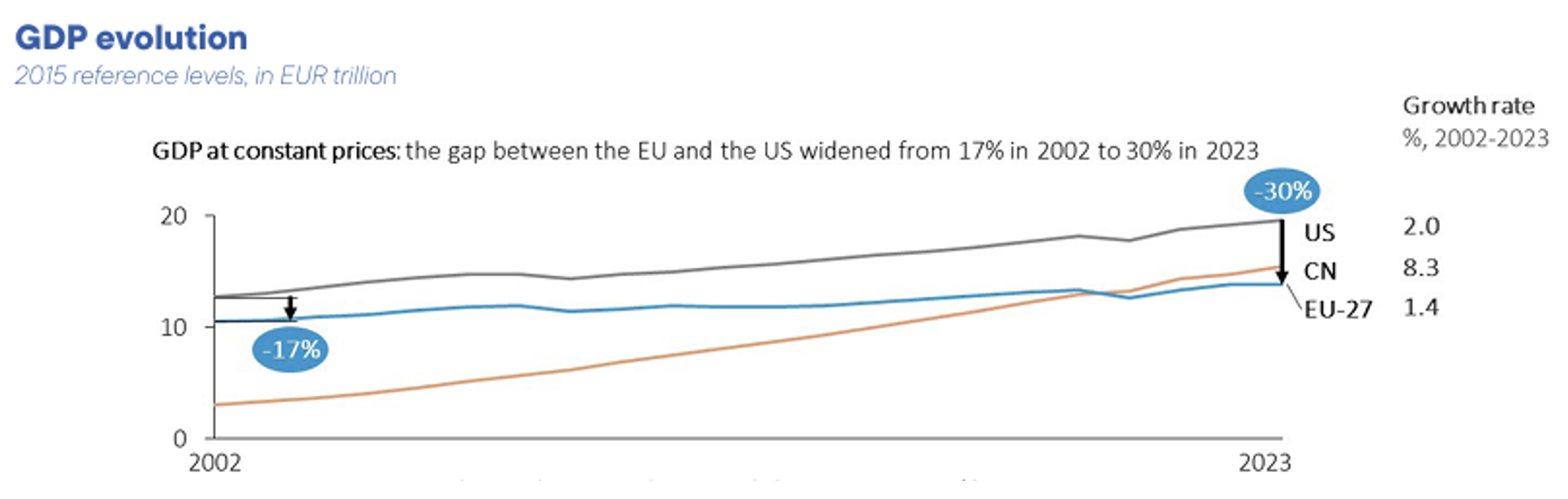

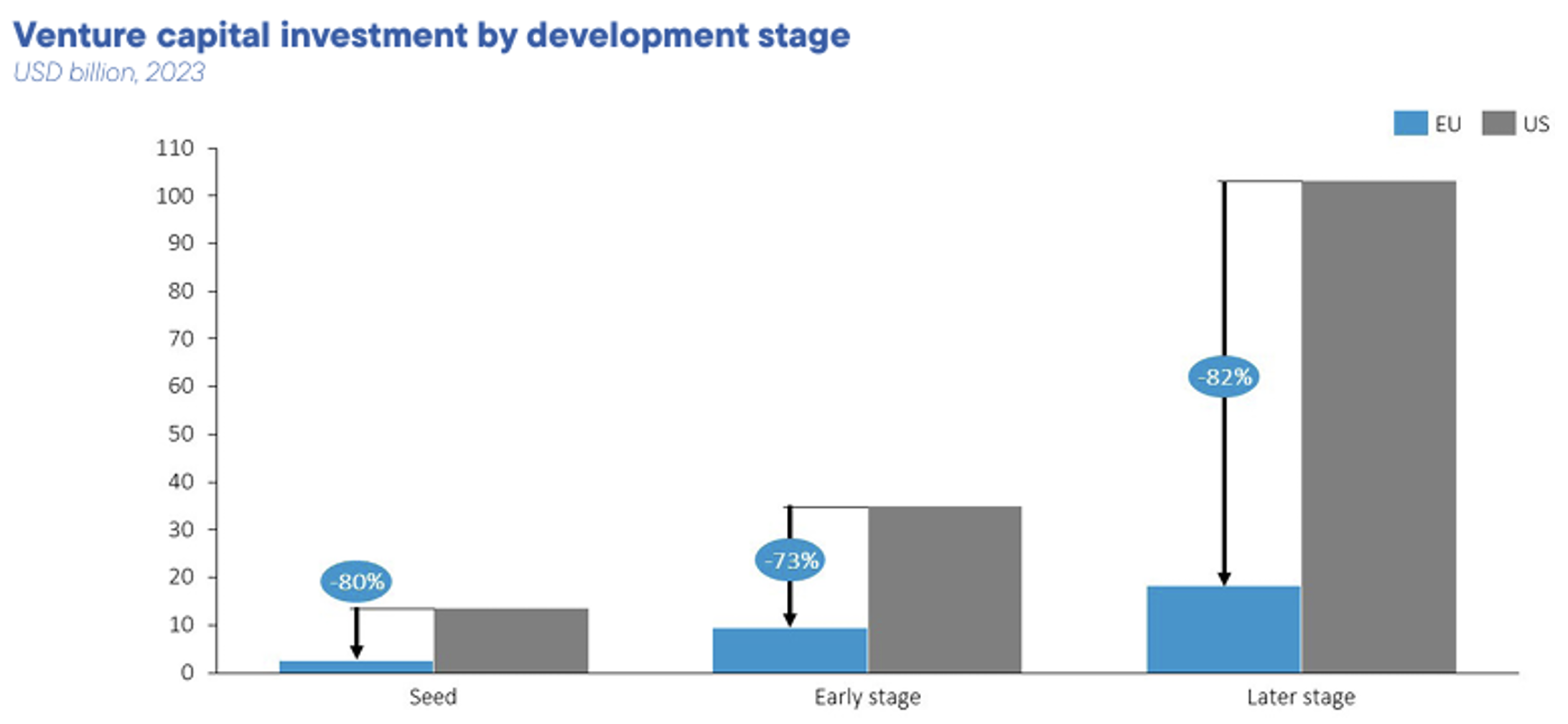

Among the culprits, writes Draghi, is a lack of productivity, caused largely by a failure to take advantage of the digital revolution of the past 20 years. He cites feeble GDP growth, abetted by a lack of innovation and risk-taking:

As an example, Draghi points out that among the world’s top 50 technology companies, only four are based in the EU.

Draghi views new growth as urgently critical for Europe, for several reasons including:

- an ageing population, to be supported by a smaller workforce (which by 2040 is projected to be shrinking by almost 2 million workers per year)

- geopolitical instability (resulting, for example, in the loss of Europe’s largest energy supplier: Russia)

- the need to address climate change

The only way for Europe to preserve its security, finance its social model and support sustainability, says Draghi, is to become more productive. To do so, he suggests fostering innovation, investing in decarbonization and increasing security. Draghi cites a Commission estimate stating that this would require the EU to invest an additional EUR 750-800 million annually, or about an additional 4.5% of GDP. To illustrate the immensity of the challenge, he points out by comparison that investment in Europe under the US Marshall Plan from 1948 to 1951 amounted to 1-2% of GDP.

His suggested additional financing would come mostly from private capital but also require direct government investment. To help unlock private capital, Draghi recommends fiscal incentives, improved capital market efficiency, the reduction of regulatory burden, and other initiatives that Commission President von der Leyen would reiterate in her instructions to Commissioner Albuquerque (mentioned above).

Regulatory burden, Draghi points out, is viewed by 60% of European companies as an obstacle to investment, and is particularly onerous for tech and startup companies. Among the contributing factors:

- the sheer volume of EU legislation

- overlap and duplication of regulatory requirements

- the lack of regulatory flexibility afforded to smaller companies

- divergence of national laws within the EU

- a lack of impact assessments at the national level

To tackle the problem, Draghi proposes some concrete measures:

- before new regulation is proposed, a six-month period of regulation “stress-testing” at the beginning of each new Commission’s term

- consolidation of EU regulation (starting with policy areas that affect EU competitiveness)

- creating a new Commission “Vice-President for Simplification”, charged with reducing regulatory burden

- fully implementing the Commission’s 2023 pledge to reduce regulatory reporting requirements by 25%

Last month, many of Draghi’s recommendations received high praise from lofty places like the European Council and von der Leyen herself. But there are also healthy skeptics, who point to practical obstacles such as Europe’s fragmented markets, challenges in mobilizing needed capital, and increasing political destabilization (the latter dramatically underlined by recent collapses of government in France and Germany).

How investment firms should react

Notwithstanding the EU’s plans to reduce burdensome compliance requirements, regulatory divergence and change will continue to impact investment firms doing business in Europe, at least in the short and medium terms. Continuing implementation and amendments to relevant regimes such as AIFMD, UCITS, MiFID and EMIR -- even if ultimately moving toward streamlined obligations -- will take years to finalize. Items to watch for next year include new technical standards, updated guidance, disclosure templates and other outputs for these regimes, as ESMA details in its 2025 Annual Work Programme.

Close attention to ESG compliance is also advised, for firms subject to EU rules. Among the strategic goals for the Commission’s new five-year term is “sustainable prosperity”, confirming that sustainability remains an inherent part of the EU’s desired mobilization toward economic growth. Meanwhile, investment firms should continue to monitor for developments, such as ESMA’s Q&As regarding sustainable fund names released earlier this month.

Interestingly, Von der Leyen recently revealed plans to combine the Taxonomy Regulation, CSRD and CSDDD into one law. While this may not directly affect investment managers’ reporting requirements under SFDR (which itself is being reviewed for major changes), it should further remind them of the need to remain alert to the ongoing evolution of ESG rules in Europe.

About Confluence

Confluence is a leading global technology solutions provider committed to helping the investment management industry solve complex data challenges across the front, middle, and back offices. From data-driven portfolio analytics to compliance and regulatory solutions, including investment insights and research, Confluence invests in the latest technology to meet the evolving needs of asset managers, asset owners, asset servicers, and asset allocators to provide best-of-breed solutions that deliver maximum scalability, speed, and flexibility, while reducing risk and increasing efficiency. Headquartered in Pittsburgh, PA, with ~700 employees in 15 offices across the United Kingdom, Europe, North America, South Africa, and Australia, Confluence services over 1000 clients in more than 40 countries. For more information, visit confluence.com